The Accountability Gap in Global Supply Chains: Why Trade Data Needs Human Rights

- Anonymous

- Dec 20, 2025

- 6 min read

Updated: Jan 5

“As we reflect on the future of trade, we should always remember its contribution to lifting living standards across the world, and that balanced approaches are needed, in order to mitigate supply chain risks without unduly compromising the benefits that come from global trade for competition, innovation, productivity, efficiency and ultimately growth.“ OECD Secretary-General Mathias Cormann

As the business environment for voluntary and regulatory reporting evolves, there still are gaps between reporting and the social supply chain context. Since the April 2013 Rana Plaza building collapse in Bangladesh, which killed over 1,100 garment workers and injured over 2,000 despite having been cleared by a social auditing entity, corporations and government have increased their attention on their social supply chain impacts and dependencies. As a result of this and similar tragedies, labor laws and policies globally, such as the EU Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (2024/1760) have increased transparency across supply chains.

Yet to date, trade data still does not integrate with social supply chain data. This means recorded trade data is absent the labor impacts that go into the production and trade of these same trade goods.

With growing attention from consumers, regulating entities, and governments on ethical sourcing, Responsible Alpha recommends that trade data databases and platforms work towards integrating social supply chain data.

The Workforce Behind the Trade: The Accountability Gap

Globally, over 450 million people work in supply chains yet these workers’ social supply chain data are not included in trade data.

Companies rationally employ workers in countries where costs of production are lower as companies’ want to lower costs to remain competitive. These choices to outsource labor can raise ethical and economic concerns.

Supply chains often include suppliers and subcontractors employing people from vulnerable groups such as women workers, migrant workers, child laborers, and people living in poverty.

Recent examples include undervalued workers in factories producing name-brand clothing and footwear, on farms harvesting crops such as cacao, tea, and tobacco, and in mines digging for metals used in electronics sold globally.

The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises on Responsible Business Conduct describes the due diligence steps to help companies address supply chain impacts yet does not describe the need to integrate trade data with social supply chain data.

Thus, trade data suffers from an accountability gap. While the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights describe how corporations can be responsible for ensuring acceptable working conditions in their supply chains, corporations often lack control or access to knowledge of how these workers are treated.

A key reason is that trade data does not integrate with social supply chain data.

Gaps in ESG Governance Monitoring & Reporting

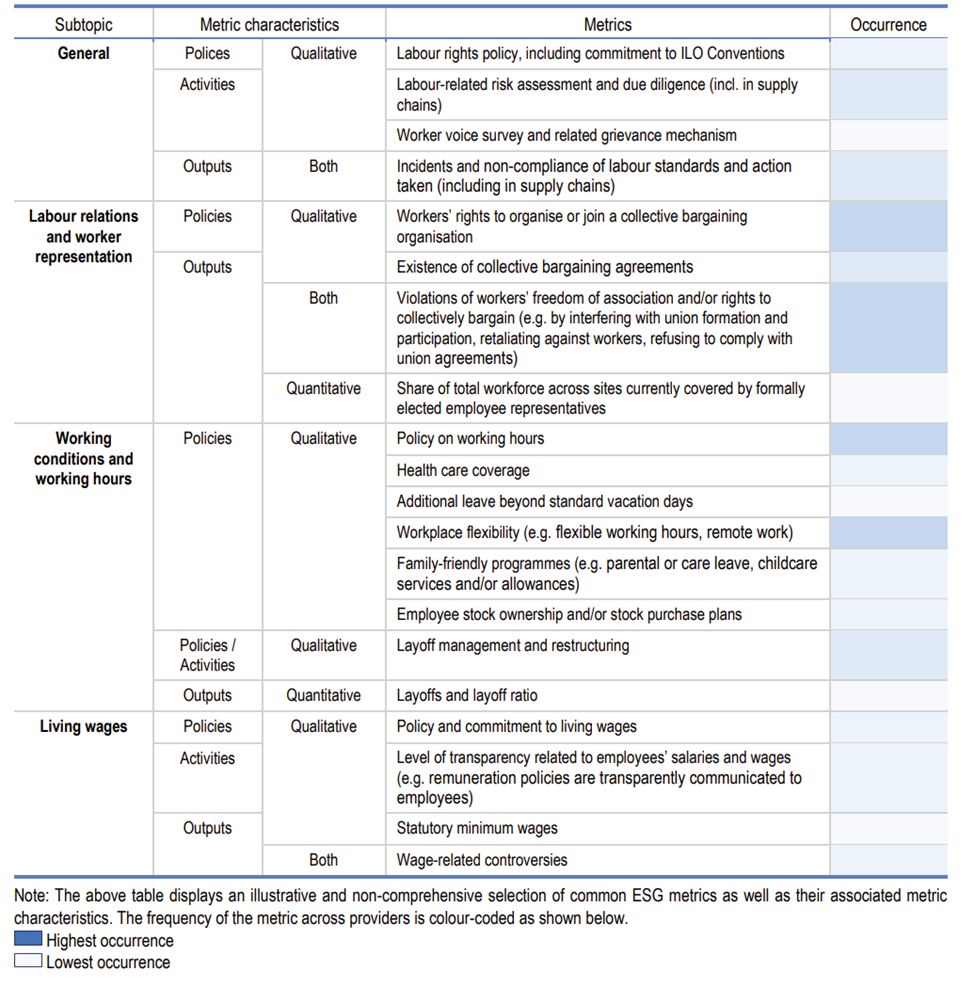

A 2025 OECD empirical analysis of over 2,000 collected metrics used in eight ESG rating products finds that simple metrics are insufficient to assess observance of OECD standards on responsible business conduct: ESG rating products tend to measure how companies manage impacts, risks, and opportunities with respect to a specific topic, irrespective of inter-topic interlinkages.

The report finds (see Figure 1) that although the coverage distribution of metrics across ESG categories are comparable, the disparity in the number of available metrics is more pronounced at the topic level. There is a divergence in the granularity of assessment across different ESG topics.

On average more than twenty metrics are used to measure performance related to Corporate Governance, Business Ethics, and Environmental Management, compared to less than five metrics for Community Relations & Impacts.

The report found eleven topics absent and not measured at all from at least one rating product, including Human Rights, Corruption, Bribery & Fraud, DEI, Corporate Responsibility, and Product Stewardship.

ESG rating products rely primarily on input-based metrics (70% of all metrics), which capture self-reported policies put in place to address potential and actual ESG impacts, risks, and opportunities, while nearly one-third (30%) of the metrics are output-based. The OECD finds (see Figure 2) that only 7% of all metrics could be associated with supply chain risk management across topics and products. Less than half of the rating products studied excluded forced and child labor metrics.

Again, ESG data and specifically ESG trade data does not integrate with social supply chain data.

Due Diligence Law Implications in International Supply Chains

In 2015, the UK enacted the Modern Slavery Act (2015), which aims to address the issue of modern slavery in business operations and their global supply chains. By “modern slavery,” the UK government refers to human trafficking, forced labor, and child labor: severe human rights violations that affect 27 million victims worldwide, driving $236 billion in illegal profits annually.

The Modern Slavery Act applies to all UK-based companies and subsidiaries that have an annual turnover of £36 million or more. It also applies to commercial organizations that do business in any part of the UK and hit the turnover threshold.

These companies must submit annual reports to the UK government which include a Transparency in Supply Chain (TISC) clause. In these reports, they must describe their risks regarding the potential for human trafficking and slavery in their supply chain. This process includes mapping out supply chains and areas – such as countries and industries – where risks may occur.

Companies must report their approach to compliance such as training staff to identify warning signs of forced labor and human trafficking. Companies also need to adopt whistleblowing policies that protect anyone in the company who reports on transgressions, including how an issue is raised and what corrective actions can occur. Furthermore, these companies must conduct audits to identify supplier noncompliance with their required Supplier Code of Conduct.

In 2024, the EU adopted the Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (CSDDD), which legally requires companies to perform due diligence processes to prevent adverse human rights and environmental impacts, namely “forced labour, child labour, inadequate workplace health and safety, exploitation of workers, and environmental impacts.” The Directive applies to all companies registered in the EU over the threshold of EUR 40 million net annual worldwide turnover, as well as smaller companies operating in the EU which generate turnover in sectors with likelihood to cause social and/or environmental damage.

Under the CSDDD, companies must establish a supply chain due diligence policy including a code of conduct describing the rules and principles to be followed by the company’s employees and subsidiaries. Companies are required describe measures taken to verify compliance with the code of conduct and to extend their application to established business relationships. Companies also need to monitor the implementation and effectiveness of their due diligence measures annually.

They need to establish a procedure for dealing with complaints and following up appropriately.

Finally, the EU Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD) requires disclosure on working conditions, wages, freedom of association, consultation with workers, and health and safety.

Again, UK Modern Slavey Act, the EU CSDDD, and the EU CSRD data not integrate with social supply chain data.

Furthermore, the Observatory of Economic Complexity and other trade data platforms such as the U.S. Census Bureau trade data platform do not integrate social supply chain data into their data visualization platforms demonstrating global imports and exports.

World Customs Organization Can Change HS Codes to Address Concerns

The World Customs Organization (WCO) deploys the Harmonized System (HS) trade data system to categorize global imports and exports into levels of granularity starting with the broader HS2 category to the HS4 and HS6 and other more specific categories. The WCO can respond to the concerns of governments and international organizations pushing for steps to counter newly emerging problems: the

For example, the global HS code system now contains categories for ozone depleting substances, precursor chemicals used to manufacture illicit drugs, hazardous wastes, chemical weapons, and narcotics.

These category codes were created by the WCO in response to international concerns in recent decades, in order to better track and regulate the flow of products that have demonstrated harmful consequences. Many international conventions, agreements, and initiatives rely on the HS to implement import and export trade regulations at borders.

The problem is that HS codes offer no way to distinguish between products from companies with strong labor codes versus those with looser criteria around worker rights.

Yet, the WCO could provide a process to review how to incorporate social supply chain data (see Figure 3) into HS codes.

Take Action

World Customs Organization: The WCO could provide a process to review how to incorporate social supply chain data into HS codes.

Trade Databases: Trade data databases and platforms can work towards integrating social supply chain data.

Comments