Bison Bond: A Financial Opportunity Whose Time Has Come

Executive Summary

North American bison (bison bison bison), which were an essential role in shaping prairie ecosystems and serving as a vital foundation for the cultural, spiritual, and economic life of many Indigenous nations, once roamed the vast grasslands of North America declining from approximately 8 million to less than 500 by the end of the 19th century (Taylor). These massive animals were not merely a food source; they were deeply woven into the cosmology, governance, and identity of countless Tribal nations across the Great Plains and beyond. The Tribal nations who suffered rapid loss of bison herds, the economic and social impacts observed today are dire: higher deaths of despair, extreme poverty, and inability to accrue wealth.

Nonetheless, impact investors can support these Tribes by providing financing resources to support ecological, economic, and societal restoration directly resulting in decreasing deaths of despair and extreme poverty via Tribal lead self-determination.

After 18 months of analysis, the authors would like to propose the development of a bison bond funding structure. The Bison Bond delivers conservation finance as a scalable, sovereign-led investment vehicle that generates competitive returns while producing measurable ecological and social impact. The prospected $100 to $150 million Sustainable Development Bond, priced at a modest premium with a 12-year tenor funds the restoration of one of the keystone species. Of this, $40 million to $60 million est. provides start-up funding for Tribal nations across the Northern Great Plains and elsewhere to strengthen their own path towards food sovereignty, improving health outcomes, and better economic outcomes for their community members.

Key Takeaways

-

Tribal bison restoration is a multifaceted movement intertwining culture, climate resilience, and economy.

-

Impact investors have a significant opportunity to support ecological and cultural restoration via various commonly used funding mechanisms.

-

Several tribes and nonprofits are already demonstrating successful, scalable models.

-

Revenue streams from bison include meat sales, ecotourism, PES (payment for ecosystem services), and live animal trade.

-

Strategic investments can catalyze long-term sustainability and sovereignty for Indigenous communities overcoming multi-generational economic, societal, and ecological harm caused by the near extinction of bison.

Introduction

For centuries, Indigenous peoples coexisted with the bison in a reciprocal relationship, guided by a worldview that saw the bison not as a commodity, but as a relative a sacred being that offered sustenance, shelter, tools, and teachings. This relationship ensured the stewardship of millions of acres of grasslands, sustained diverse ecological systems, and formed the basis of thriving Indigenous economies.

Tribal nations of the Northern Great Plains, once the tallest people in the world before the near extinction of bison, the generations born were among the shortest. In fact, current formerly bisonreliant Tribal nations have between 20% to 40% less income per capita than the average Tribal nations

(Feir et al).[1]

However, the colonial expansion of the United States in the 19th century brought catastrophic disruption to this balance. Driven by a desire to expand territory, suppress resistance, and make way for settler agriculture, the U.S. government and private interests waged a deliberate campaign to eliminate bison herds. Military commanders and policymakers recognized that by destroying the bison, they could destroy the lifeways and food systems of the Plains tribes. What followed was a statesanctioned ecological genocide: more than 8 million bison were slaughtered in the 13 years from 1870 to 1883.

The bison herds future collapsed in 1871 when tanners in Europe developed a commercial method of tanning bison hides (Taylor)[2]. Just in one year, in 1875, 1 million bison hides were imported by European nations. shipped from the United States to France and England alone.

By 1879, the southern herd was extinct (Hornaday).[3]

The loss devastated ecosystems, led to soil erosion and grassland degradation, and plunged Indigenous nations into hunger, displacement, and forced dependency.

In fact, the data is clear. The near extinction of bison directly drove associated social and economic collapse of the Northern Great Plains Tribal Nations.

-

Health: Tribal nations that lost the bison most quickly suffered a 5 to 9 cm (2 to 4 inch) decline in height relative to those that lost the bison slowly. This decline more than eliminates the initial height advantage of bison-reliant people.[4]

-

Income: Per capita income on reservations comprised of previously bison-reliant societies was approximately 30% lower in 2000, compared with reservations comprised of non-bison-reliant peoples.6, [5]

-

Rapid-Loss Tribal Nations: Tribal Nations who lost bison rapidly, 1870 to 1883, have 40% lower incomes than average Tribal Nations who did not suffer from bison loss.[6]

-

Economic Decline: Tribes’ reservations which overlapped with bison historical range have $2,500 lower income per capita in 2000 compared to those whose territories did not overlap with bison’s original range.

-

Economic Loss: Losing the bison as part of a slaughter is associated with $3,800 lower income per capita, which is 30% to 40% of the average Tribal income on reservation in 2000 of $10,500

(Figure 1).

-

Worse Off Than Neighbors: Formerly bison-reliant Tribes make less on average than nearby non-tribal counties (Figure 2).

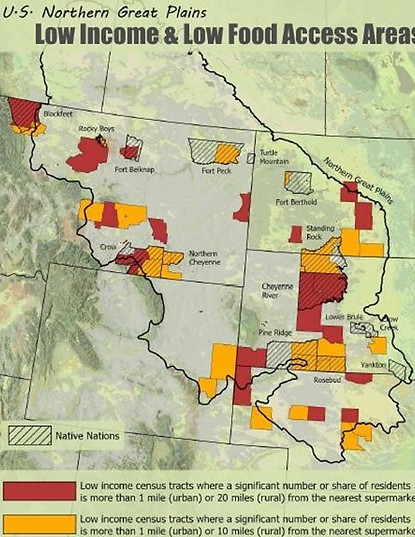

Figure 1: Percent Households Enrolled in Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP). Data: USDA Economic Research Service Food Access Research Atlas (2019) https://ers.usda.gov/dataproducts/food-access-research-atlas

Figure 2: Lowest Ranked Counties in the U.S. by U.N. Human Development Index. Data: USDA Economic Research Service Food Access Research Atlas (2019) https://ers.usda.gov/dataproducts/food-access-research-atlas

-

Greater Deaths of Despair: Deaths of despair, homicide, alcoholism, diabetes, and suicide, are significantly greater for bison-reliant Tribes compared to non-bison reliant Tribes.

-

Lack of Food Access: Formerly bison-reliant Tribes currently face today still lack food access (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Low Income and Low Food Access Tribes in the Northern Great Plains. Data: USDA Economic Research Service Food Access Research Atlas (2019) https://ers.usda.gov/data-products/foodaccess-research-atlas

Yet, the story does not end in disappearance. Today, we are witnessing a powerful resurgence. Across North America, Tribal nations are reclaiming their roles as bison caretakers and ecological stewards. On Tribal lands in Montana, South Dakota, Nebraska, and beyond, bison are returning not just as animals on the land, but as symbols of Indigenous resilience and resurgence. These efforts are part of a broader movement to restore land-based lifeways, revitalize ceremonial practices, and rebuild Tribal economies. Bison restoration is about healing of land, of people, and of cultural memory.

While many of these efforts are driven by community will, cultural continuity, and ancestral knowledge, they are often under-resourced and face persistent barriers: fragmented land ownership, infrastructure gaps, regulatory complexity, and lack of access to flexible capital. Most projects rely heavily on grants, limiting their ability to scale or plan long-term.

This report examines how impact investing can help bridge that gap. It highlights how values-aligned capital structured with patience, humility, and deference to Indigenous governance can support the growth of bison herds, the restoration of prairie ecosystems, and the development of Tribal enterprises based on bison meat, ecotourism, cultural products, and ecosystem services. Through case studies, financial tools, and practical pathways for collaboration, we aim to show how investors can support this resurgence not as benefactors, but as respectful partners in a movement rooted in justice, regeneration, and self-determination.

Pathways: Bison Instead of Cattle

The reintroduction of bison to Tribal lands is not merely a matter of restoring a lost species, it is a profoundly political, cultural, and spiritual act. And there is an immediate economic opportunity to reintroduce bison (Figure 4). For Indigenous nations, bison are not livestock or commercial assets; they are sacred beings, kin, and partners in a relationship that spans thousands of years. Their near extermination during the 19th century represented not just ecological destruction but a direct assault on Indigenous sovereignty, food systems, spiritual traditions, and land-based lifeways. As such, their return today signals far more than the reappearance of a keystone species. It is an act of decolonization. It is about restoring balance between people and land, between spiritual and material worlds, and between past and future.

Figure 4: Northern Great Plains Cattle Ranching on Tribal Lands. Data: USDA Economic Research Service Food Access Research Atlas (2019) https://ers.usda.gov/data-products/food-accessresearch-atlas

Decolonization in this context means more than removing colonial systems; it means revitalizing Indigenous ones. Restoring bison helps reestablish ancient governance systems based on caretaking, reciprocity, and interdependence. It revitalizes language, ceremony, and education tied to the land. It empowers Indigenous communities to define development on their own terms centered not on extraction and profit, but on relational accountability and collective well-being. Bison are integral to this process because they once sustained entire societies physically, culturally, and spiritually. Their return, therefore, helps restore the complex systems both ecological and cultural that were violently disrupted.

Equally important, bison restoration is a critical strategy for food sovereignty. Centuries of imposed dependency, forced commodity food programs, and disconnection from traditional diets have left many Tribal communities facing high rates of diet-related illnesses and food insecurity. Bison offer a nutrient-dense, culturally significant, and locally produced food source that is aligned with Indigenous values. Bringing bison back to the center of community food systems is not only about nutrition, but also about dignity, cultural continuity, and healing from historical trauma.

In the face of accelerating climate change, bison also represent a model of resilience. Unlike introduced cattle, bison evolved in harmony with the North American grasslands. Their natural grazing behaviors regenerate native grasses, improve soil health, sequester carbon, and enhance biodiversity. By mimicking the migratory patterns of historic herds, Indigenous-led bison restoration contributes to climate adaptation in ways that are low-tech, cost-effective, and deeply rooted in place-based knowledge.

Furthermore, bison restoration is catalyzing Tribal economic revitalization. From bison meat production and tourism to hide crafts and ecological service markets, bison-centered enterprises are emerging that not only generate income but align with cultural values. These are not extractive industries, they are regenerative, circular, and often community owned.

Yet impact investors can support this multidimensional movement. We propose that when investment capital is guided by Indigenous leadership, values, and timelines, it can play a meaningful role in supporting land acquisition, herd expansion, infrastructure, and enterprise development. Crucially, this support must not impose outside metrics or control it must instead be rooted in authentic partnership. Bison restoration is not a conventional development project. It is a profound opportunity to contribute to systems change that honors Indigenous sovereignty, repairs ecological relationships, and builds a future grounded in intergenerational justice.

Current Conditions

Despite the growing visibility and momentum behind bison restoration, many Tribal-led efforts face persistent and significant challenges. While the cultural, ecological, and economic case for bison restoration is strong, the operational reality on the ground is often constrained by a lack of resources, limited infrastructure, and systemic barriers. These obstacles slow progress, limit scale, and place additional strain on communities that are already overextended. Yet, despite these conditions, Indigenous communities across North America continue to lead the resurgence of bison herds, guided by ancestral knowledge, cultural continuity, and deep commitment to healing both the land and their people.

One of the most pressing barriers is access to land. While many Tribes hold legal title to sizable areas, the usable land base for bison restoration is often fragmented due to jurisdictional complexity, leasing arrangements, or lack of fencing and grazing infrastructure. Some lands are held in trust by the federal government, limiting what kinds of development or improvements can take place without bureaucratic approval. In other cases, suitable lands may be encumbered by competing uses or degraded by decades of misuse. Without sufficient contiguous, well-managed territory, it is difficult to maintain healthy and self-sustaining herds.

A second major challenge is infrastructure. Restoring bison is not simply a matter of turning animals loose on the land. It requires fencing, water access points, veterinary care, corals, feed systems, and in many cases, processing and cold storage facilities to support meat production. These capital needs are significant, especially for programs operating on tight budgets. In addition, transportation of live bison or meat products across Tribal, state, and federal boundaries often runs into regulatory hurdles, including USDA inspection requirements and disease control protocols that were not designed with Tribes in mind.

Most programs today rely heavily on grants and nonprofit support, which, while invaluable, come with limitations. Grant cycles are short, reporting requirements are burdensome, and funds often cannot be used for critical activities like land purchase or revenue-generating business development. Nonprofit models, while impactful, can be overly reliant on philanthropy and leave programs vulnerable to shifts in donor priorities or economic downturns. This funding landscape makes long-term planning difficult and inhibits the growth of sustainable Tribal enterprises.

Despite these challenges, Indigenous bison programs continue to grow. The drivers are clear: the cultural and spiritual importance of bison, the ecological benefits they bring to the land, and the urgent need for food sovereignty and local economic development. In many cases, it is the strength of community will, intergenerational vision, and ancestral connection to the bison that propels these efforts forward, even in the absence of adequate capital.

This report argues that impact investment, when aligned with Indigenous leadership and priorities, can play a catalytic role in overcoming these barriers. Unlike conventional investment or restricted philanthropy, impact capital can be structured to be patient, flexible, and responsive to community timelines. By partnering with Tribes in respectful, equity-centered ways, investors can help scale restoration projects in ways that do not compromise sovereignty, self-determination, and sustainability.

How Impact Investing Can Help

Impact investing offers a compelling and necessary alternative to traditional grantmaking by providing catalytic capital that fuels long-term vision, infrastructure development, and income generation. While grants remain important, they are often short-term, restrictive, and unsuitable for projects that require sustained investment over multiple years. Impact capital, in contrast, can be designed to align with Indigenous priorities, governance structures, and timelines unlocking potential that conventional funding mechanisms cannot reach.

When structured with care and respect, impact investing supports Tribal Nations and partner organizations in expanding bison herds, restoring native grasslands, and building regenerative, bisonbased economies. This approach emphasizes flexibility and collaboration, recognizing that economic development in Indigenous communities must be rooted in cultural continuity and sovereign decisionmaking.

Financial tools such as low-interest loans, revenue-sharing agreements, or credit enhancements can empower Tribes to fund fencing, water infrastructure, herd management, and meat processing facilities without ceding control to outside investors. Importantly, these tools must be co-designed with Indigenous stakeholders to ensure that they are non-extractive and supportive of self-determined development. Unlike conventional capital models that demand rapid growth or high returns, impact investing in this context requires patience, humility, and a willingness to prioritize relationship over transaction.

By investing in bison restoration, impact investors have the opportunity to contribute to a systems-level transformation that touches ecology, culture, food sovereignty, and local economies. This is not just about funding a species comeback it’s about restoring Indigenous relationships to land, economy, and future generations. With the right financial structures in place, bison restoration can become a model for regenerative development that benefits communities, ecosystems, and ethical investors alike.

Theory of Change and Examples

Our theory of change begins with the foundational principle of Tribal sovereignty the inherent right of Indigenous nations to govern their lands, resources, and futures. Bison restoration is not simply an ecological project; it is a sovereignty project. When Indigenous communities have decision-making power over how land is used and how economies are structured, the outcomes are more holistic, resilient, and culturally grounded.

From this base, the theory builds through ecological restoration, recognizing bison as a keystone species whose presence revitalizes ecosystems. As natural grazers, bison help regenerate native grasses, cycle nutrients through the soil, improve water infiltration, and support the return of pollinators and other species. Their reintroduction strengthens grassland health, sequesters carbon, and enhances biodiversity making them a vital climate adaptation tool.

This ecological revitalization directly contributes to community health. Bison provide a culturally relevant, nutrient-rich source of food, helping to address diet-related diseases that disproportionately affect Indigenous populations. Moreover, the return of bison supports mental, emotional, and spiritual health by reconnecting people especially youth and elders to traditions, ceremonies, and land-based practices.

These interlinked outcomes then fuel local economic development. Bison herds enable Tribes to develop enterprises such as meat production, cultural tourism, hide processing, and ecosystem services. These enterprises create jobs, retain wealth locally, and reduce dependence on extractive industries or external control.

Impact investments can support every stage of this cycle from acquiring and fencing land, to building meat processing facilities, launching PES (Payment for Ecosystem Services) projects, and funding intergenerational programs that engage Tribal youth in restoration work.

Real-world examples across the Northern Great Plains from Rosebud to Fort Peck demonstrate how this integrated systems approach works in practice. When supported by values-aligned capital, bison restoration becomes a driver of sovereignty, sustainability, and intergenerational healing.

Restoration Examples

InterTribal Buffalo Council

A coalition of 82 federally recognized Tribes, the ITBC is a national leader in bison restoration. It provides technical assistance, policy advocacy, and live bison transfers. ITBC's cooperative model is scalable and rooted in self-determination.

Defenders of Wildlife

Through policy and financial support, Defenders help Tribes build infrastructure and secure funding. Their role exemplifies how non-Tribal allies can support without controlling Indigenous restoration work.

American Prairie NGO

American Prairie’s private conservation efforts intersect with bison restoration. They offer lessons on a scale, infrastructure, and the challenge of aligning private landholding with public interest.

Others

Smaller initiatives like the Sicangu Lakota’s Rosebud herd, Fort Peck Tribes in Montana, and the Blackfeet Nation’s Iinnii Initiative show diverse, community-centered approaches with strong ecological and educational impacts.

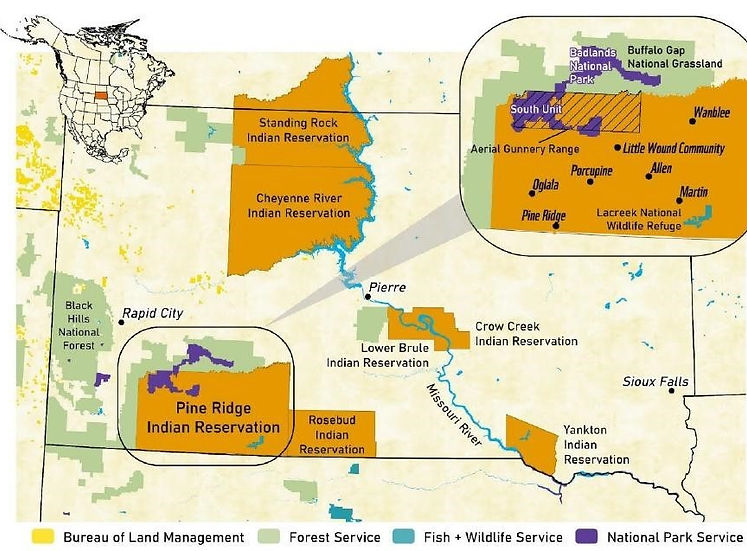

Opportunity in Northern Great Plains

The Northern Great Plains region offers expansive grasslands ideal for bison restoration. Opportunities exist to fund herd expansion, fencing, regenerative grazing systems, processing facilities, and carbon and biodiversity credit development. Bison restoration here can serve as a model for global land-based climate adaptation.

SME (Small and Medium Enterprises)

Tribal bison programs can incubate SMEs around meat production, ecotourism, cultural experiences, and land stewardship. These enterprises generate local jobs, support youth engagement, and diversify Tribal economies.

Bison Meat Sales

Bison meat is a premium product with a growing market. Tribes are increasingly seeking vertical integration from raising to processing to branding to retain value within the community and tell their own food sovereignty stories.

Products

Beyond meat, bison provide hides, skulls, leather goods, and educational materials. These products can reinforce cultural identity while generating supplemental revenue streams.

PES (Payment for Ecosystem Services)

Bison support ecosystem services such as carbon sequestration, water infiltration, and biodiversity. PES markets represent a major untapped opportunity for Tribal bison programs, with careful attention to ownership and measurement protocols.

Ecotourism

Bison-based tourism, including wildlife viewing, cultural interpretation, and heritage trails, can be a significant income source. Ecotourism must be locally controlled and aligned with cultural values.

Live Bison Sale

Live bison sales offer immediate revenue and support broader restoration. Tribes with established herds often assist newer programs by selling or gifting animals, forming an informal but powerful restoration network.

Example Current Tribal Opportunities

Impact investors can play a key role by offering patient capital, supporting infrastructure, underwriting PES frameworks, and building equitable partnerships. Investments must be co-designed with Tribal stakeholders to ensure alignment with sovereignty, values, and long-term sustainability.

There are many immediate opportunities for impact investors to support bison reintroduction in the Northern Great Plains. The following programs were described in the Returning Buffalo with Native Nations: Forum Notebook which occurred in 2023. To summarize:

-

The Bison Bond delivers conservation finance as a scalable, sovereign-led investment vehicle that generates competitive returns while producing measurable ecological and social impact. The prospected $100 to $150 million Sustainable Development Bond, priced at a modest premium with a 12-year tenor funds the restoration of one of the keystone species. Of this, $40 million to $60 million est. provides start-up funding for Tribal nations across the Northern Great Plains and elsewhere to strengthen their own path towards food sovereignty, improving health outcomes, and better economic outcomes for their community members.

Blackfeet Buffalo Program: Rematriation of Iinniiwa in the Ninaiistáko Region of Traditional Siksikaitsitapi Lands

Figure 5: Blackfeet Buffalo Program: Rematriation of Iinniiwa in the Ninaiistáko Region of Traditional Siksikaitsitapi Lands[7]

-

Tribal led.

-

Native Nation(s): Amskapi Piikani (Blackfeet Nation) and Blackfoot Confederacy (Siksikaitsitapi).

-

Tribal Organizations: Blackfeet Nation (BFN) Tribal Business Council, Blackfeet Nation Buffalo. Program and Blackfeet Nation Fish and Wildlife Department.

-

Location: Northwestern Montana (Glacier and Pondera Counties) and Southern Alberta.

-

Bison: Expand upon approximately 100 bison that were returned to Blackfeet homelands in 2016 from Elk Island National Park in Alberta.

-

Land for Bison: 30,000 acres set aside by Tribal Council resolution at the base of Ninaiistáko (Chief Mountain) and a larger landscape inclusive of the transboundary Waterton-Glacier International Peace Park, a UNESCO World Heritage site (Figure 5).

-

Startup Costs: $2,300,000 est.

The Blackfeet Buffalo Program is focused on restoring free-roaming bison to traditional Blackfeet lands in the Ninaiistáko region (Chief Mountain), blending ecological renewal with cultural revitalization. Through rematriation efforts, youth training, and habitat monitoring, the program reconnects the community with the Iinniiwa (bison) while navigating challenges like fragmented land tenure and climate change. With nearly 40,000 acres set aside, the initiative emphasizes biocultural restoration and community healing, but requires sustained funding for infrastructure, staff, equipment, and land acquisition to support herd expansion and public engagement.

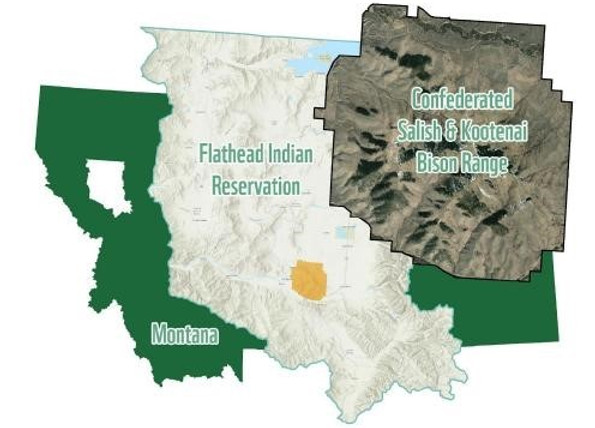

CSKT Bison Range: Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes

Figure 6: CSKT Bison Range: Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes.

-

Tribal led.

-

Native Nation(s): Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes (Selis, Qlispe, Ksanka People) of the Flathead Reservation (Sqelixw/Aqlsmaknik).

-

Tribal Organizations: Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes Bison Range.

-

Location: Flathead Reservation, Montana.

-

Bison: 350+.

-

Land for Bison: 18,766 acres on the CSKT Bison Range + Additional Pastures on Tribal Lands for CSKT Production Herd (Figure 6).

-

Startup Costs: $13,300,000 est.

After regaining full control of the National Bison Range in 2022, the CSKT launched a comprehensive effort to manage a conservation herd while planning a new production herd and a culturally centered visitor center. Their goals integrate bison ecology research, food sovereignty, education, and tourism. Key needs include GPS collaring for research, infrastructure upgrades, and development of a new interpretive center to tell the CSKT story and engage Tribal youth and elders. Invasive species, staff capacity, and infrastructure maintenance are ongoing challenges that require external support.

Fort Belknap Buffalo Program: Aaniiih and Nakoda Nations

Figure 7: Fort Belknap Buffalo Program: Aaniiih and Nakoda Nations

-

Tribal led.

-

Native Nation(s): Aaniiih and Nakoda Nations, Fort Belknap Indian Community.

-

Tribal organization(s): Fort Belknap Buffalo Program.

-

Location: Fort Belknap Reservation, Montana.

-

Bison: 2,000+ stable herd size.

-

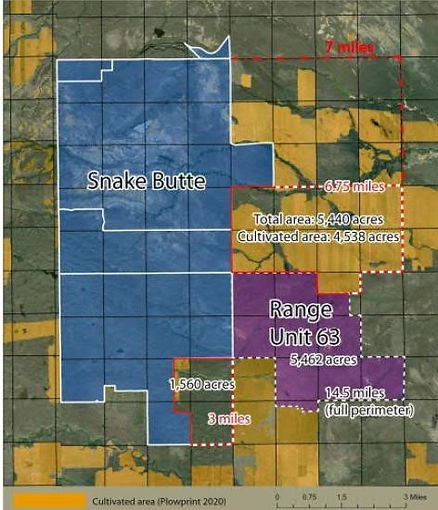

Land for Bison: Currently 23,064 acres with the potential to add 17,942 acres of habitat over the next 5 years through reseeding, lease acquisition, and infrastructure development. This will bring the total acres managed for bison at Fort Belknap to 41,006. (Figure 7).

-

Startup Costs: $4,500,000 est.

This program focuses on restoring native grasslands and expanding bison habitat across the Fort Belknap Reservation. With over 23,000 acres currently managed and plans to add nearly 18,000 more, the project emphasizes ecological stewardship, food security, and youth engagement through education. The initiative includes reseeding farmland, building wildlife-friendly fencing, and constructing facilities for education and operations. Critical challenges include a lack of centralized leadership and facilities, but recent governance reforms and partnerships position the program for long-term growth.

Fort Peck Buffalo Program: Fort Peck Assiniboine and Sioux Tribes

Figure 8: Fort Peck Buffalo Program: Fort Peck Assiniboine and Sioux Tribes

-

Tribal led.

-

Native Nation(s): The Fort Peck Assiniboine and Sioux Tribes.

-

Tribal Organizations: Fort Peck Tribes Fish and Game Department.

-

Location: Fort Peck Reservation, Montana.

-

Bison: 600.

-

Land for Bison: 1,350 acres directly, innumerable with ever-growing ITBC Membership.

-

Startup Costs: $8,600,000 est.

Fort Peck operates the only Tribal Phase 3 quarantine facility for Yellowstone bison, playing a critical role in redistributing genetically valuable bison to Tribes across the continent. While facilitating disease testing and logistics in collaboration with the InterTribal Buffalo Council (ITBC), the Fort Peck program currently bears most of the operational costs. Their vision includes expanding to 150,000 acres, improving quarantine infrastructure, and developing meat processing capacity to support local food sovereignty efforts. The program requires significant investment to maintain and scale its impact.

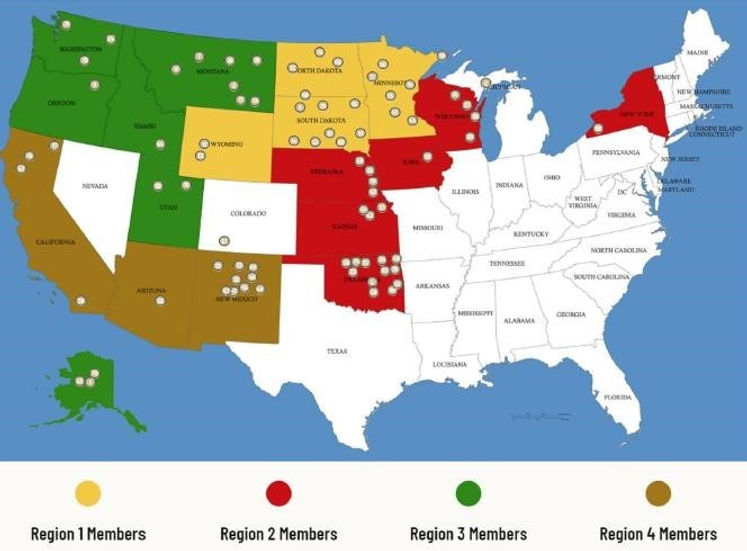

ITBC Buffalo Learning Center

Figure 9: ITBC Buffalo Learning Center

-

Tribal led.

-

Native Nation(s): Numerous.

-

Tribal Organizations: InterTribal Buffalo Council.

-

Location: Centrally located in Fort Pierre, South Dakota to serve 83 ITBC Member Nations.

-

Bison: 200 directly, 10,000 over 5 years through ITBC Surplus Program.

-

Land for Bison: 17,000 acres currently managed for 300 disease free Yellowstone bison including 320-acre quarantine facility (currently holding 150 bison but capacity is 600 bison) where 1 year of assurance testing occurs before redistribution to Tribes (Figure 9).

-

Startup costs: $4,200,000 est.

The InterTribal Buffalo Council is creating a Buffalo Learning Center in South Dakota to serve as a national hub for Tribal bison management training, youth education, and equipment sharing. With plans to house education and research herds, the center aims to build Tribal capacity and foster intergenerational knowledge transfer. This initiative is designed to address the growing needs of ITBC’s 83 member Tribes, offering infrastructure, curriculum, and workforce development tools. However, realizing this vision will require over $4.5 million in funding for facility development, staffing, and operations.

Thunder Valley Community Development Corporation: The Oónakižiŋ (Stronghold) Buffalo Homeland

Figure 10: Thunder Valley Community Development Corporation: The Oónakižiŋ (Stronghold) Buffalo Homeland

-

Tribal led.

-

Native Nation(s): Oglala Lakota Nation.

-

Tribal Organizations: Thunder Valley Community Development Corporation.

-

Location: Pine Ridge Reservation, South Unit Badlands National Park, South Dakota.

-

Bison: 390.

-

Land for Bison: 39,904 acres of habitat (approx. 26,000 grazeable acres) (Figure 10).

-

Startup costs: $1,700,000 est.

Thunder Valley Community Development Corporation is restoring bison to a 39,904-acre lease on the Pine Ridge Reservation, reclaiming lands lost during WWII and repurposed by the U.S. government. Their long-term lease allows for the reintroduction of up to 390 bison. This effort blends cultural healing, regenerative agriculture, and community resilience through infrastructure development, ecological monitoring, and educational programming. Overcoming outdated lease systems and securing necessary fencing, staff housing, and program support are key hurdles.

Wind River Tribal Buffalo Initiative - Eastern Shoshone and Northern Arapaho Tribes: Restoring Buffalo as Wildlife

Figure 11: Wind River Tribal Buffalo Initiative - Eastern Shoshone and Northern Arapaho Tribes: Restoring Buffalo as Wildlife

-

Tribal led.

-

Native Nation(s): Eastern Shoshone and the Northern Arapaho Tribes.

-

Tribal Organizations: Wind River Tribal Buffalo Initiative.

-

Location: Wind River Reservation, Wyoming.

-

Bison: 1,000.

-

Land for Bison: 17,000 acres (Figure 11).

-

Startup costs: $17,300,000 est.

The Wind River initiative seeks to restore bison as wildlife under Tribal law, reversing long-standing classification as livestock. With newly acquired 17,000 acres of contiguous habitat, the initiative aims to expand the bison population to 1,000 and eventually connect to over 60,000 acres. This cross-Tribal collaboration integrates conservation, cultural renewal, and legal reform while creating opportunities for youth education and land stewardship. Major needs include perimeter fencing, educational facilities, staffing, and operational funds to support expansion and sustainability.

Funding a Feasibility Study Describing Financing Options

Impact investors can step and provide funding to describe potential funding options for Tribal Nations to finance bison rematriation resulting in subsequent ecological, economic, and societal restoration.

An Example: The Bison Bond Sketch

The Bison Bond is a Sustainable Development Bond designed to produce social, environmental, and commercial outcomes. It will create economic opportunities, promote native-led sustainability initiatives, fortify tribal self-determination, and help revive the historic interdependence with bison that have supported Indigenous societies in North America. Bond proceeds will expand the bison economy.

The goal of structuring and issuing a Bison Bond is to directly support the following outcomes:

-

Increase the population, health, and vitality of the nation’s wild conservation and commercial bison herds.

-

Expand the size of tribal land ownership and property management.

-

Increase the scale and capacity of USDA’s Indigenous bison commercial and food harvesting programs, as well as total revenue from bison harvesting, live bison sales, and bison product sales.

-

Enhance the availability and awareness of eco-tourism opportunities and bison-related cultural experiences.

-

Expand programs of conservation nonprofit organizations, including financial and capacity resources for related tribal community efforts around bison.

-

Broaden the vitality of economic, social, health, and education programs in Native American communities.

The bond will align with and support UN Sustainable Development Goals and Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework, including Target 22, which focuses on inclusion for Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities.

Bison Bond Size

The prospected $100 to $150 million Sustainable Development Bond, priced at a modest premium with a 12-year tenor funds the restoration of one of the keystone species. Of this, $40 million to $60 million est. provides start-up funding for Tribal nations across the Northern Great Plains and elsewhere to strengthen their own path towards food sovereignty, improving health outcomes, and better economic outcomes for their community members.

Demand

Responsible Alpha and colleagues surveyed the following institutions who demonstrated significant demand for the bond:

-

New York Federal Reserve Bank.

-

Minneapolis Federal Reserve Bank.

-

State Street Global Advisors.

-

F.L. Putnam.

-

CFA Society Boston.

-

Farmer Mac.

Institutional Investor Survey Results

Demand is clearly present for this type of financial instrument. As of spring 2024:

-

370 bonds issued in 2023 used proceeds for biodiversity conservation (ICE).

-

There is more than $85 billion in municipal green bonds outstanding (S&P).

Below is a summary of findings from a survey conducted by Responsible Alpha and colleagues in 2024 to assess preliminary purchasing demand and preferences from institutional fixed income portfolio managers.

-

5 institutional fixed income asset firms were interviewed.

-

Titles were Portfolio Manager, Product Manager, Credit and Risk Manager, ESG Portfolio Manager, Director Fixed Income Research, and Assistant VP Sales.

-

All agreed that 10+ term made sense. They liked the term of the bond was structured to exceed political cycles. They supported the larger amount of $150 million plus stating that this bond proposed hypothetically as a sustainability linked bond (SLB) municipal revenue debt where infrastructure being funded was ecosystem restoration, thus having very strong Environmental + Social credentials made the bond very appealing. In particular, they liked the first loss guarantee/risk taken by philanthropy/government overlaid with government issuance.

-

The credit rating as long as investment grade and bond was not more expensive versus similar issuances.

-

They thought that this was an "easy win" for them to invest in as long as the underlying aggregated SME credits were managed using appropriate tools.

-

They liked the Tribal Nation oversight.

-

In particular, a global top 5 assets under mgt. firm said they would like to help out with the structuring of the bond as they would make it even more appealing to their portfolio managers and their asset owners whose mandates, they have either won or are competing to win.

Key Assumptions

-

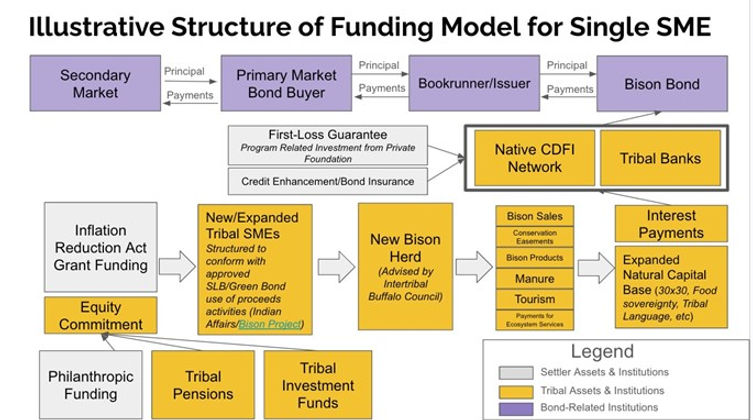

First-loss guarantee from foundations and impact investors to mitigate risks to Tribal Nations. • Obtaining credit enhancements and bond insurance to mitigate risks to Tribal Nations

-

Assets generated must be owned and overseen by Tribal Nations.

-

Bond proceeds must flow through Native CDFIs and Tribal Banks.

-

Use of proceeds must conform to approved SLB/Green Bond activities.

-

Interest and principal payments must not encumber tribal economies.

-

External funders and supporters must not distort tribal intentions.

Below is an illustrative bond program example. It is not the proposed funding model.

Possible Structures: Tribal Municipal Bonds (Section 7871(a) through (e)) and Tribal Economic Development Bonds (Section 7871(f))

Tribal Governments can initiate two types of tax-exempt bonds:

-

Tribal bonds that need the requirements under Section 7871(a) through (e).

-

Tribal Economic Development Bonds that need the requirements of Section 7871(f).

From 1987 through 2010, Tribal governments issued an average of about $157 million annually in tax-exempt bonds for a total of about $3.76 billion in 321 total transactions.[1]

Tribal Municipal Bonds: 7871 (a) through (e)

There are three basic rules for tribal bonds under Section 7871(a) through (e).

• First: The issuer must be a federally recognized Tribal Government or subdivision thereof. The Indian Tribal Government Tax Status Act of 1982 added two new sections. 7701(a)(40) and 7871 pertaining to the status of Tribal Government.

A Tribal Government qualifies as the issuer of tax-exempt bond under Section 7701(a)(40) where the definition of the term Indian Tribal Government is the governing body of any tribe, band, community, village or group of Tribes or if applicable Alaskan natives that is determined by the secretary of the Treasury after consultation with the Secretary of the Interior to exercise governmental functions.

Regulations provide that before an Indian Tribal Government can be treated as a state, the purposes of issuing tax-exempt bonds under Section 103, it must be designated by revenue procedure.

The most recent revenue procedure designating Indian Tribal Governments is Revenue Procedure 200855 and it was coordinated with a list of federally recognized Tribes published by the Department of Interior, Bureau of Indian Affairs. In general, any Tribal entity that appears on the most recent list published by the Department of the Interior in the federal register is designated in Indian Tribal Government for purposes of Section 7701(a)(40).

-

Second: All (or most) proceeds must be used in the exercise of any essential governmental function which does not include any function not customarily performed by a state or local government with general taxing powers.

For tribal bonds issued under Section 7871(a) through (e), the bonds must meet a test of the essential governmental function test. The essential governmental function test has been in place since the original enactment of Section 7871 as a temporary provision of the code by the Indian Tribal Government Tax Status Act in 1982.

Section 7871(e) provides that the term essential governmental function does not include any function which is not customarily performed by state local government with general taxing powers. One that was added by the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1987, the House report expressed that the issuance of bonds to finance commercial or industrial facilities such as private rental housing, cement factories or mirror factories is not included within the scope of the essential governmental function even if the bonds are technically not private activity bonds. The House report added that only those activities that are customarily financed with governmental bonds, which are school, roads and governmental buildings, are intended to be within the scope of the essential governmental function test.

In applying the essential governmental function test, Section 7871(c)(1) requires that a tax-exempt obligation of an Tribal Government be part of an issue substantially all of the proceeds of which are to be used and exercised at any essential governmental functions. Regulations provide the general rules that the substantially all test is satisfied if 90% or more of the proceeds of the bonds issued are used for an essential governmental function. Note that there are other specific rules for determining what substantially all is.

-

Third: Issuers cannot issue Tax Exempt Private Activity Bonds except to finance the construction of qualified manufacturing facilities that meet certain use, location, ownership and employment requirements.

There are restrictions under 7871(a) through (e) that prohibit Indian Tribal Governments from issuing private activity bonds. Private activity bonds are bonds issued by a state or local government that meet either the private loan financing test or both of the private business tests.

The private loan financing test asks whether the proceeds of the bonds will be used to make or finance loans directly or indirectly to non-governmental persons. If this test is met, the bonds are private activity bonds. The two private business tests are the private business use test and a private security or payment test. The private business use test generally asks if the proceeds or if the facility finances private proceeds will be used in a trade or business carried on by any person other than a governmental unit.

The private security or payment test generally seeks to determine if the debt service on issue either is derived from payments made with respect to property used in a private trade or was secured by an interest in or by payment in respect of property used in private trade or business. If both the private business use test and the private security or payment test are met, then the bonds are private activity bonds.

There is an exception to the general rule. The private activity bond issued by Indian Tribal Governments are not tax exempt. The exception is found in Section 7871(c)(3) and applies to bonds to issue, are qualified to finance qualified manufacturing facilities.

Tribal Economic Development Bonds (TED bonds): Section 7871(f)

TED Bonds are relatively new category of taxes and bonds that can be issued by Indian Tribal Government. TED Bonds were created by the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009, and they are governed by Section 7871(f). In the Recovery Act, $2 billion of volume cap was provided to be allocated among tribes for TED Bonds.

After the Recovery Act was enacted, the IRS issued Notice 2009-51. The notice set forth the application procedures for tribes wanting to apply for an allocation of TED Bond volume cap. In 2009 and 2010, the IRS allocated the $2 billion volume cap in two batches, approximately $1 billion in each batch. Under the rules that existed then, the volume cap allocations where limited to $30 million or less.

Most of the volume cap allocations or about $1.8 billion or 90 percent were forfeited so the IRS went back to the drawing board and in July of 2012, published procedures for applying for an allocation of the forfeited volume cap. Notice 2012-48 revised many of the application procedures and rules. For instance, there are no deadlines for application now. In addition, the allocation limit has been altered so that now a tribe can obtain a much larger allocation of volume cap.

The current rules generally limit a tribe's aggregate volume cap allocation to the greater 20% of the total unallocated volume cap or a $100 million. The IRS updates this every two months.

To apply for an allocation of volume cap, the applicant must meet certain requirements.

-

First: The application must be submitted by a federally recognized Indian Tribal Government. This program is not open to state-recognized tribes unless they are also federally recognized tribes.

-

Second: The application must describe in a reasonable detail the project or projects that will be financed by the TED Bonds.

-

Third: The application must include the expected costs of the projects.

-

Fourth: The application must include a plan for financing the project(s). The documentation from an independent third party showing the bonds are expected to be marketable.

-

Fifth: This is also a statutory requirement. The projects must be located and finally within that applicant Tribal reservation. If there is a joint project between tribes, the project must be located within one or more of the applicants’ reservations.

TED Bonds are subject to a few limitations and standard tribal bonds are not.

-

TED Bonds limitations include the tribe must obtain volume cap.

-

TED Bonds must expressly be designated as a TED Bond.

-

TED Bonds do not require an essential governmental function to be financed; the proceeds of TED Bonds cannot be used to finance gaming. See IRS Notice 2009-51.

The benefit of TED Bonds is that as opposed to standard tribal bonds, they can be used to finance any project or activities to which state or local government could issue tax exempt bonds under Section 103. TED bonds can be qualified private activity bonds provided they satisfy the same requirements the qualified private activity bonds of state and local governments must satisfy.

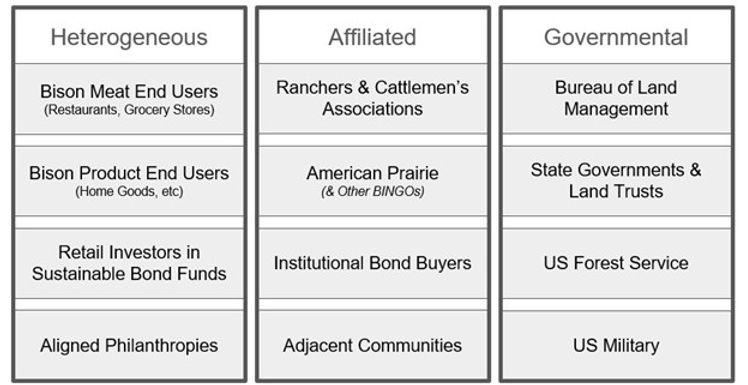

Non-tribal Stakeholder Group Matrix

Collaboration

Funding the acquisition of new and expansion of tribal lands is a core program focus. These lands would support multiple revenue producing activities to grow The Bison Economy, as well as increasing bison and other wildlife range connectivity. Bond program revenue producing tribal activities include, as example: • Commercial and retail bison meat sales:

-

Starting and expanding initiatives started by the USDA Indigenous food sovereignty program.

-

Live bison sales:

-

Distributing wild bison to ranches, parks and private ownership.

-

-

Eco tourism and native cultural activities, for example:

-

Bison habit wildlife viewing and hiking on tribal owned or controlled properties with lodges, cabins, and camping. Non-native fee-paying visitors are the target market.

-

Cultural tours and ceremonies targeting non-native fee-paying visitors.

-

-

Buffalo product sales:

-

Hides, skulls, bone products and mounts.

-

-

Ecosystem commodity and services generation and sales:

-

Carbon and biodiversity credits sold the private sector.

-

This Bison Bond will serve as the lead financing mechanism of the new Great Bison Initiative, a multi-year blended finance conservation and community program to access funding from private sector and institutional investors in the United States and Canada. The initiative will help create new public-privatephilanthropic collaborations to help finance The Bison Economy.

Feasibility Study

Bond structure and program feasibility and design to be performed by capital markets advisor, initiative director and hired legal and tax advisory (Bond Group). It will require funding for the consulting fees to compensate for time and expenses by the Bond Group. Funding could be in the form of a grant, foundation support or from a development budget by an entity such as Dept. of Interior. Accessing direct funding from DOI could significantly shorten the time to conduct the feasibility study. It’s possible to structure the return of feasibility study funding from the proceeds of a Bison Bond issuance.

Below is a list of outcomes that would result from a 4-month feasibility study conducted on bond covenants, revenue models, partner and stakeholder engagement, and issuance structure.

Feasibility Outcomes

-

Target issuance terms: size, maturity, coupon, rating, etc.

-

Alignment to UN SDGs and Global Biodiversity Framework.

-

Alignment to International Capital Market Association (ICMA) Green and Social Bond Principals.

-

Engagement of key stakeholder constituencies, including tribal-led financial institutions to ensure their maximal involvement.

-

Validate non-market stakeholder groups.

-

Management plan for key stakeholder constituencies.

-

Tax exempt bond status with Tribal Governments.

-

Payback through revenue model.

-

Create program working model.

-

Conduct needs assessment with existing and expansion bison herds.

-

Validate any payment for ecosystem services model with aligned partners.

-

Identification of bond issuer and underwriter – Examples: USDA, Tribal Financial Institution or NGO.

-

Provisional bond structure and issuance schedule.

-

Establish bond program partnerships and stakeholder organization agreements or MOUs.

-

Revision of MOU with Great Plains Conservation Network.

-

Expanded demand side engagement with potential bond buyers.

-

Draft Bond Group consultant success fee terms.

-

Go-to-market plan.

In addition to bond structuring and revenue model information, the feasibility study would create program KPIs and targets.

Examples

-

Conservation bison population increase: “+30% by 2030”.

-

Acres of bison conservation increase: “+30% by 2030”.

-

Jobs created.

-

Participants in youth education and work programs.

-

USDA food sovereignty program bison population increases.

-

USDA food sovereignty program revenue increases.

-

Increase in bison live sales.

-

Non-native fee-paying visitors.

-

Non-native fee-paying guest lodging capacity.

-

Tons of carbon sequestered in carbon credit generation.

-

Acres and metrics in biodiversity credit projects.

-

UN Sustainable Development Goal alignment: SDGs 1, 3, 4, 8, 12, 15, and 17.

-

Global Biodiversity Framework Targets: 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 9, 11, 16, 19, and 22.

Opportunity Summary

To fully realize the vision of bison restoration, each initiative must navigate complex and often underfunded implementation pathways. While the cultural, ecological, and economic motivations are deeply rooted, the practical work of fencing land, acquiring bison, training staff, and building processing or visitor infrastructure requires capital often far beyond what is currently available through grants or Tribal budgets. Each project operates within its own unique landscape of opportunity and constraint, but all share the need for patient, flexible funding tailored to Indigenous priorities. The following section presents theoretical funding outlines for each of the eight Tribal-led bison restoration efforts. These models draw on public data, forum materials, and project-specific documentation to estimate infrastructure, staffing, equipment, and operational costs offering a starting point for how impact capital might support scalable, long-term restoration grounded in sovereignty and sustainability.

The prospected $100 to $150 million Sustainable Development Bond, priced at a modest premium with a 12-year tenor funds the restoration of one of the keystone species. Of this, $40 million to $60 million est. provides start-up funding for Tribal nations across the Northern Great Plains and elsewhere to strengthen their own path towards food sovereignty, improving health outcomes, and better economic outcomes for their community members.

The investment thesis is compelling and clear. Commercial bison meat commands premium pricing with demand consistently outpacing supply. Eco-tourism to tribal lands generates substantial visitor spending with minimal infrastructure requirements. Carbon and biodiversity credits from restored grasslands provide additional revenue streams in rapidly expanding environmental markets. Live bison sales to ranches and conservation programs maintain steady pricing power. Each revenue stream operates independently, creating natural portfolio diversification and risk mitigation.

Investment Drivers

-

Institutional Demand: There is significant institutional demand to fund a bison bond structure.

-

Carbon Revenue Acceleration: Restored grasslands generate verified carbon credits trading at $7 to $15 per ton with 20 plus year revenue visibility, providing stable cash flows independent of agricultural commodity cycles.

-

Recession-Resistant Revenue: Eco-tourism, meat sales, and ecosystem services create counter-cyclical revenue streams that strengthen during economic uncertainty when consumers prioritize authentic experiences and sustainable consumption.

-

Policy: Federal carbon policies, USDA Indigenous food sovereignty programs, and state-level bison restoration incentives create multiple revenue enhancement opportunities with limited policy risk.

The structure of the bond eliminates barriers that have constrained Indigenous-led conservation projects. First-loss guarantees and credit enhancements protect bondholders and ensure tribal nations retain full ownership and control of assets. Mandatory capital flows through Native CDFIs and tribal banks strengthen Indigenous financial institutions while maintaining sovereignty.

Consumer demand for sustainable, locally sourced protein continues to accelerate. Carbon markets are maturing with improving price signals. Most critically, tribal nations across the Northern Great Plains are prepared to move forward with restoration projects pending adequate capitalization.

The eight tribal initiatives profiled represent immediate deployment opportunities for bond proceeds, each with established leadership, identified land bases, and operational readiness. Each project will launch with or without optimized financing. The Bison Bond simply enables them to achieve greater scale, faster implementation, and stronger financial sustainability.

For investors, this represents rare access to an asset class combining infrastructure-like stability with growth equity upside potential. For tribal nations, it provides patient capital without compromising sovereignty. For the bison, it offers the most realistic pathway to population.